Blog: Electrifying Transportation and Shifting Travel Patterns can Cut CO2 while Saving the US Trillions of Dollars

Widespread adoption of electric vehicles—combined with a shift in travel modes towards more walking, cycling, and transit use—can help ease the climate crisis, improve quality of life, and save Americans money. A key to shifting travel modes to less automobile use is making biking, walking, and transit safer and more convenient by redirecting infrastructure investments and making urban areas more compact. When compared to the trajectory we are currently on, faster vehicle electrification and a shift in travel modes could save the US economy a cumulative $13 trillion, save the average urban resident $2,000 per year, reduce transportation inequities, and make cities more livable.

A recent study, from ITS-Davis and the Institute for Transportation & Development Policy, explores four scenarios and identifies steps that can move us in the direction of cost savings and lower emissions of greenhouse gasses and pollutants:

- In the Business as Usual scenario, vehicle electrification and a shift in travel modes occur gradually, according to current trends and policies.

- In the Electrification scenario, the transition to electric vehicles is faster – as fast as experts consider possible.

- In the Mode Shift scenario, people use non-automobile travel modes at a “maximum feasible” level as these modes become more feasible and appealing.

- In the fourth Electrification + Shift scenario, these last two scenarios are combined.

Electrification

The Electrification scenario has sales of new light-duty vehicles (cars and light trucks) reaching 60% electric nationwide by 2030 and 100% by 2050. The US reached about a 7.6% electric (and plug-in hybrid) vehicle market share in 2023, which is a good start, but there is a ways to go.

Achieving the Electrification scenario will probably require that eventually: 1) electric vehicles provide significant ownership savings compared to gasoline vehicles; 2) electric vehicle ranges are sufficient to meet all driving situation needs, and 3) public charging becomes widely available at or close to most homes and in public roadside locations convenient for long trips. If these conditions can be met, then the main challenge will be a marketing one: convincing Americans that EVs are desirable and meet their needs.

Mode Shift

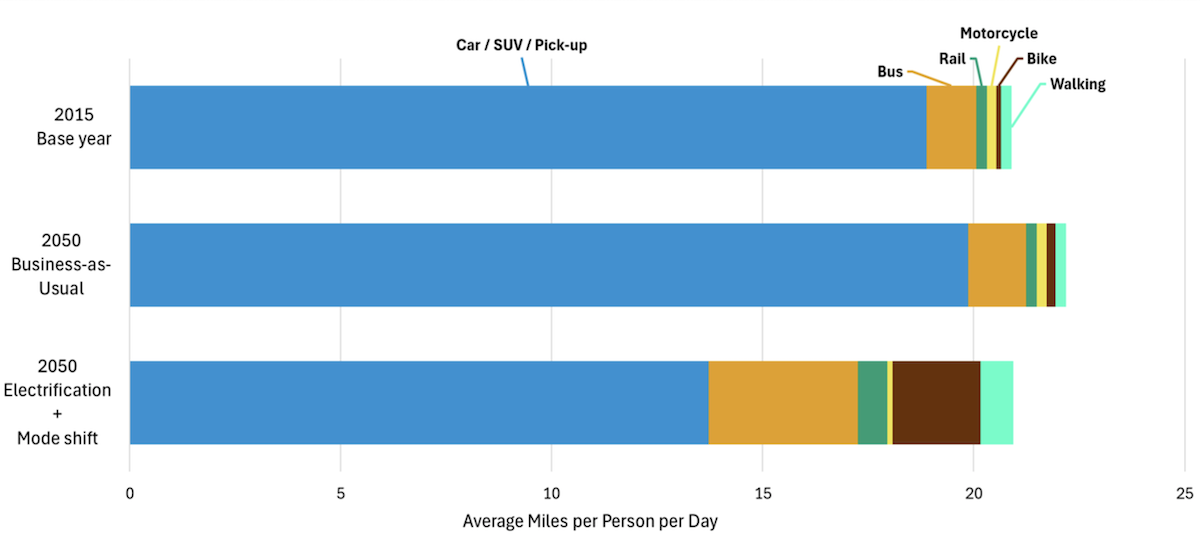

Getting Americans to reduce their dependence on cars and use other modes of transportation may seem harder than going electric, though the changes envisioned in our Mode Shift scenario are not massive. In this and the combined Electrification + Shift scenario, urban car, SUV, and personal pick-up truck (light-duty vehicle) travel in 2050 would be about 25% less than in the Business as Usual scenario. This reduction goes along with much better infrastructure to increase travel by transit, biking, and walking. And even with the increases in infrastructure and operations for these modes, the shift will save governments and individuals considerable funds and provide an important range of health benefits, which are described in the report.

Miles traveled using each mode according to year and scenario; “Bike” includes electric bikes.

But what changes are needed to make such a mode shift possible? It will require increasing density and mixed-use development in cities and suburbs, coupled with more sidewalks, protected bike lanes, and safer streets with slower traffic. All of this will encourage people to choose to walk or ride a traditional or electric bike or an e-scooter. Electric bikes could play a growing role for trips under 5 miles if roadways are designed to make this safe. On the transit side, there is a critical need for more frequent service, which could be made possible by increased population density and would make using transit more appealing and logical. People will need to consider these modes convenient and safe and at least give them a try. Having the right infrastructure and shorter trips is a prerequisite.

American cities are already getting denser, but the trend is gradual. The average neighborhood has about 12,500 people per square mile today, and we’re on track to increase to 13,500 by 2050. But achieving the Mode Shift and combined scenario will require reaching an average density of nearly 17,000 people per square mile by 2050. This doesn’t mean that everywhere will look like New York City—it just means that the average American city will look more like Los Angeles than Atlanta, the average neighborhood more like Arlington, Virginia than Arlington, Texas.

Small and large cities will have a density and layout more resembling a walkable town than spread out areas of housing, miles from shopping plazas. Such moderate densities can be achieved through public policy that is already being adopted in some states. Examples include “missing middle” policies to legalize multi-family housing up to six or eight units on all lots and removal of requirements for a minimum of off-street parking. The densified cities in the mode shift scenarios will not require anyone to leave or redevelop their home against their wishes—it will only create a supply of walkable neighborhoods that are currently in high demand.

The expansion of public transit and protected bike and pedestrian ways will require investment, but the funds required are less than what is currently spent on building and maintaining road infrastructure. The estimated cumulative savings for national, state, and local governments between 2024 and 2050 would be $2 trillion. Similarly, much of the annual savings of $2000 for urban residents would come from the reduction in car ownership.

Action Plan

The most important point is that we need citizens and governments committed to making this happen, voting for it, and re-allocating sufficient funds. The report on our study provides a list of policy strategies at federal, state, and local levels that would enable these changes. Some examples include:

- Modestly increase the tax on internal combustion engine cars to help fund incentives to lower the costs of electric vehicles and to fund transit and infrastructure for cycling and walking.

- Support equitable placement of public charging points and charging in multi-unit dwellings.

- Reallocate federal and state transportation budgets and road space to walking, cycling, and public transport.

- Entirely stop building new roads or expanding existing ones. Use the funding to maintain and improve the capacity of existing roads by reallocating space to more efficient modes, like cycling and public transport.

- Along major roads, build a connected, integrated network of bus rapid transit lines—buses that operate like light rail: have a dedicated center-running lane, take priority at intersections, and are boarded from stations.

- Redirect existing subsidies for fossil fuels to the expansion and decarbonization of the nation’s electricity system to support clean transportation and other uses.

This transformation is possible. Cities around the country have already proven that it can be done. In only two years, Seattle transformed its bus network such that 64% of residents live near a bus line with ten-minute service or better, up from only 25% before the change, leading to increased ridership. Arlington, Virginia demonstrated the importance of rapid transit: by routing a Metro line through commercial neighborhoods and building density around the stations. Arlington was able to dramatically increase population and tax revenue without any increase in traffic. In the future, cities around the country could replicate this success using affordable bus rapid transit instead of rail. The state of Minnesota is debating an act that could remove parking minimums all across the state, cutting required parking lot construction, and thus making additional space available for housing, shops, and walking.

In 30 years, our cities could be greener, more walkable, more efficient, less congested, quieter, and more affordable. We could save money for the public and private sectors. We could reduce air pollution, social segregation, and the cost of living. All that’s needed is the collective willingness to act.

——————–

Lewis Fulton is Director of the Energy Futures Program at ITS-Davis.